Giant squid, once believed to be mythical creatures, are squid of the Architeuthidae family. They are deep sea dwellers that can grow up to the size of a bus being the largest cephalopod (octopus, cuttlefish, squid) and the largest mollusk on Earth.

Nature

Family

The taxonomy of the giant squid, as with many cephalopod genera, has not been resolved. The rarity of observations of specimens and the extreme difficulty of observing them alive, tracking their movements, or studying their mating habits prevent a complete understanding. Lumpers and splitters may propose as many as eight species or as few as one without much genetic or physical basis. The broadest list is:

- Architeuthis dux, "Atlantic Giant Squid"

- Architeuthis hartingii

- Architeuthis japonica

- Architeuthis kirkii

- Architeuthis martensi, "North Pacific Giant Squid"

- Architeuthis physeteris

- Architeuthis sanctipauli, "Southern Giant Squid"

- Architeuthis stockii

In Cephalopods: A World Guide (2000), Mark Norman writes the following:

- "The number of species of giant squid is not known although the general consensus amongst researchers is that there are at least three species, one in the *Atlantic Ocean (Architeuthis dux), one in the Southern Ocean (A. sanctipauli) and at least one in the northern Pacific Ocean (A. martensi)."

Description/Morphology

- The giant squid has a long torpedo-shaped body or mantle (torso), eight arms and two longer and thinner tentacles which are used to bring food to the mouth. The arms and tentacles account for much of the squid's great length, so giant squid are much lighter than their chief predators, sperm whales.

- But is still the second largest mollusc and the second largest of all extant invertebrates. It is only exceeded in size by the Colossal Squid, Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni, which may have a mantle nearly twice as long. Several extinct cephalopods, such as the Cretaceous Vampyromorphid Tusoteuthis and the Ordovician Nautiloid Cameroceras may have grown even larger.

- Based on the examination of 105 specimens and of beaks found inside sperm whales, giant squid's mantles are not known to exceed 2.25 m (7.4 ft) in length. Including the head and arms, but excluding the tentacles, the length very rarely exceeds 5 m (16 ft). Maximum total length, when measured relaxed post mortem, is estimated at 13 m (43 ft) for females and 10 m (33 ft) for males from caudal fin to the tip of the two long tentacles. Giant squid exhibit sexual dimorphism. Maximum weight is estimated at 275 kg (606 lb) for females and 150 kg (331 lb) for males. There have been claims reported of specimens of up to 20 m (66 ft), but no animals of such size have been scientifically documented.

- The inside surfaces of the arms and tentacles are lined with hundreds of a sub-spherical suction cups, 2 to 5 cm (1 to 2 in) in diameter, each mounted on a stalk. The circumference of these suckers is lined with sharp, finely serrated rings of chitin. The perforation of these teeth and the suction of the cups serve to attach the squid to its prey. It is common to find circular scars from the suckers on or close to the head of sperm whales that have attacked giant squid.

- Giant squid have small fins at the rear of the mantle used for locomotion. Like other cephalopods, giant squid are propelled by jet — by pushing water through its mantle cavity through the funnel, in gentle, rhythmic pulses. They can also move quickly by expanding the cavity to fill it with water, then contracting muscles to jet water through the funnel. Giant squid breathe using two large gills inside the mantle cavity. The circulatory system is closed, which is a distinct characteristic of cephalopods. Like other squid, they contain dark ink used to deter predators.

- Giant squid have a sophisticated nervous system and complex brain, attracting great interest from scientists. They also have the largest eyes of any living creature except perhaps colossal squid — over 30 cm (1 ft) in diameter. Large eyes can better detect light (including bioluminescent light) which is scarce in deep water. Its beak is strong enough to cut a steal cable.

- Giant squid and some other large squid species maintain neutral buoyancy in seawater thanks to the ammonium chloride solution which flows throughout their body and is lighter than seawater. This unlike fish, which use a gas-filled swim bladder. The solution tastes somewhat like salmiakki and makes giant squid unattractive for general human consumption.

- Like all cephalopods, giant squid have organs called statocysts to sense their orientation and motion in water. The age of a giant squid can be determined by "growth rings" in the statocyst's "statolith", similar to determining the age of a tree by counting its rings. Much of what is known about giant squid is based on estimates of the growth rings and from undigested beaks found in the stomachs of sperm whales.

Reproduction

- Little is known about the reproductive cycle of giant squid. It is thought that they reach sexual maturity at about 3 years; males reach sexual maturity at a smaller size than females. Females produce large quantities of eggs, sometimes more than 5 kg, that average 0.5-1.4 mm long and 0.3-0.7 mm wide. Females have a single median ovary in the rear end of the mantle cavity and paired convoluted oviducts where mature eggs pass exiting through the oviducal glands, then through the nidamental glands. As in other squid, these glands produce a gelatinous material used to keep the eggs together once they are laid.

- In males, as with most other cephalopods, the single, posterior testis produces sperm that move into a complex system of glands that manufacture the spermatophores. These are stored in the elongate sac, or Needham's sac, that terminates in the penis from which they are expelled during mating. The penis is prehensile, over 90 cm long, and extends from inside the mantle.

- How the sperm is transferred to the egg mass is much debated, as giant squid lack the hectocotylus used for reproduction in many other cephalopods. A team of Spanish scientists at the Institute of Marine Research in Vigo developed a new theory from 5 the analysis of 5 specimens that they found ashed ashore on beaches on the Bay of Biscay. One of the two males washed ashore was found to have been accidentally inseminated - backing the findings of research in previous strandings.

- And scientists now believe the males had either accidentally inseminated themselves during "violent" lovemaking sessions with females or been inseminated by other males after "bumping" into them in the dark depths of the ocean.

- The researchers state "Although mating has never been observed in giant squid, it is thought that what happens is that the male injects his sperm packages into the female's arms. The process is likely to be a fairly violent affair as the female is probably not that keen on being injected. This is a problem for the amorous male as females are normally a third bigger than they are.

- "But males get round their inferior size by being endowed with a particularly long penis, which means they can inject the female without having to get too close to her chomping beak. The male's sexual organ is actually a bit like a high-pressure fire hose and is normally nearly as long as his body - excluding legs and head.

- "But having such a big penis does have one drawback: it seems that co-ordinating eight legs, two feeding tentacles and a huge penis, whilst fending off an irate female, is a bit too much to ask, and one of the two males stranded on the Spanish coast had accidentally injected himself with sperm packages in the legs and body. And this does not seem to have been an isolated incident since two of the eight males that had stranded in the north-east Atlantic before had also accidentally inseminated themselves."

GIANT squid are not the only members of the natural world to display unusual sexual behaviour. In Australia, the male Yellow-footed Antechinus - a mouse-like marsupial - goes through such a frenzy of mating that they die of sexual stress. The female praying mantis often eats her partner during or after sex, while homosexual behaviour is also known in geese, ostriches, cichlid fish, rats and monkeys.

Friends/Predator/Preys

- Recent studies show that giant squid feed on deep-sea fish and other squid species. They catch prey using the two tentacles, gripping it with serrated sucker rings on the ends. Then they bring it toward the powerful beak, and shred it with the radula (tongue with small, file-like teeth) before it reaches the esophagus. They are believed to be solitary hunters, as only individual giant squid have been caught in fishing nets.

- Adult giant squid's only known predators are sperm whales and possibly Pacific sleeper sharks, found off Antarctica, but it is unknown whether these sharks hunt squid, or just scavenge squid carcasses. Juveniles are preyed on by deep sea sharks and fishes. Because sperm whales are skilled at locating giant squid, scientists have tried to observe them to study the squid.

Places

Giant squid are very widespread, occurring in all of the world's oceans. They are usually found near continental and island slopes from the North Atlantic Ocean, especially Newfoundland, Norway, the northern British Isles, and the oceanic islands of the Azores and Madeira, to the South Atlantic around southern Africa, the North Pacific around Japan, and the southwestern Pacific around New Zealand and Australia. Specimens are rare in tropical and polar latitudes. Adults are found deep in the ocean, 200 to 1,000 meters (700 to 3,300 feet) (These are called the "epipelagic" and "mesopelagic" zones). Also found at the bottom in the bathyal zone - which can be 4,000 meters (13,300 feet) deep. Its biological system is not compatible with warm water, most specimens that have been found have probably been too close to the surface and died.

History/Beliefs

Culture

Tales of giant squid have been common among mariners since ancient times, and may have led to the Norwegian legend of the kraken, a tentacled sea monster as large as an island capable of engulfing and sinking any ship. Japetus Steenstrup, the describer of Architeuthis, suggested a giant squid was the species described as a sea monk to the Danish king Christian III c.1550. The Lusca of the Caribbean and Scylla in Greek mythology may also derive from giant squid sightings. Eyewitness accounts of other sea monsters like the sea serpent are also thought to be mistaken interpretations of giant squid.

Sightings

- Fewer than 600 specimens of giant squid have been recorded around the world since the 16th century, with the majority of landings and strandings in the north-east Atlantic and off the coasts of New Zealand and Australia.

- Steenstrup wrote a number of papers on giant squid in the 1850s. He first used the term "Architeuthis" (mistakenly spelled Architeuthus) in a paper in 1857. A portion of a giant squid was secured by the French gunboat Alecton in 1861 leading to wider recognition of the genus in the scientific community. From 1870 to 1880, many squid were stranded on the shores of Newfoundland. For example, a specimen washed ashore in Thimble Tickle Bay, Newfoundland on November 2, 1878; its mantle was reported to be 6.1 m (20 ft) long, with one tentacle 10.7 m (35 ft) long, and it was estimated as weighing 2.2 tonnes. In 1873, a squid "attacked" a minister and a young boy in a dory in Bell Island, Newfoundland. Many strandings also occurred in New Zealand during the late 19th century.

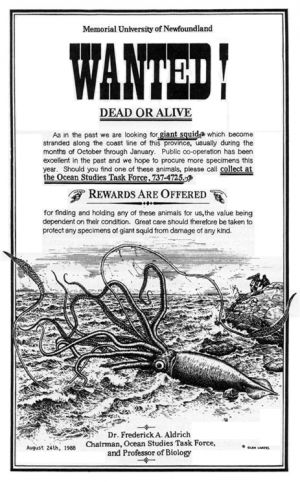

- Although strandings continue to occur sporadically throughout the world, none have been as frequent as those at Newfoundland and New Zealand in the 19th century. It is not known why giant squid become stranded on shore, but it may be because the distribution of deep, cold water where squid live is temporarily altered. Many scientists who have studied squid mass strandings believe that they are cyclical and predictable. The length of time between strandings is not known, but was proposed to be 90 years by Architeuthis specialist Frederick Aldrich. Aldrich used this value to correctly predict a relatively small stranding that occurred between 1964 and 1966.

- The search for a live Architeuthis specimen includes attempts to find live young, including larvae. The larvae closely resemble those of Nototodarus and Moroteuthis, but are distinguished by the shape of the mantle attachment to the head, the tentacle suckers, and the beaks.

- The first photographs of a live giant squid in its natural habitat were taken on September 30, 2004, by Tsunemi Kubodera (National Science Museum of Japan) and Kyoichi Mori (Ogasawara Whale Watching Association). Their teams had worked together for nearly two years to accomplish this. They used a five-ton fishing boat and only two crew members. The images were created on their third trip to a known sperm whale hunting ground 970 km (600 mi) south of Tokyo, where they had dropped a 900 m (2953 ft) line baited with squid and shrimp. The line also held a camera and a flash. After over 20 tries that day, an 8 m (26 ft) giant squid attacked the lure and snagged its tentacle. The camera took over 500 photos before the squid managed to break free after four hours. The squid's 5.5 m (18 ft) tentacle remained attached to the lure. Later DNA tests confirmed the animal as a giant squid.

- On September 27, 2005, Kubodera and Mori released the photographs to the world. The photo sequence, taken at a depth of 900 m (2953 ft) off Japan's Ogasawara Islands, shows the squid homing in on the baited line and enveloping it in "a ball of tentacles." The researchers were able to locate the likely general location of giant squid by closely tailing the movements of sperm whales. According to Kubodera, "we knew that they fed on the squid, and we knew when and how deep they dived, so we used them to lead us to the squid." Kubodera and Mori reported their observations in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society.

Among other things, the observations demonstrate actual hunting behaviors of adult Architeuthis, a subject on which there had been much speculation. The photographs showed an aggressive hunting pattern by the baited squid, leading to it impaling a tentacle on the bait ball's hooks. This may disprove the theory that the giant squid is a drifter which eats whatever floats by, rarely moving so as to conserve energy. It seems that the species has a much more belligerent feeding technique.

- In December 2005, the Melbourne Aquarium in Australia paid AUD$100,000 for the intact body of a giant squid, preserved in a giant block of ice, which had been caught by fishermen off the coast of New Zealand's South Island that year.

- In early 2006, another giant squid, later named "Archie", was caught off the coast of the Falkland Islands by a trawler. It was 8.62 m (28 ft) long and was sent to the Natural History Museum in London to be studied and preserved. It was put on display on March 1, 2006 at the Darwin Centre. The find of such a large, complete specimen is very rare, as most specimens are in a poor condition, having washed up dead on beaches or been retrieved from the stomach of dead sperm whales.

Art / Fiction

Cultural depictions

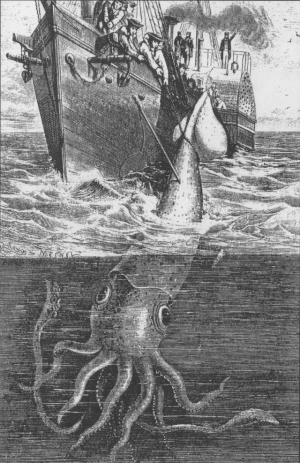

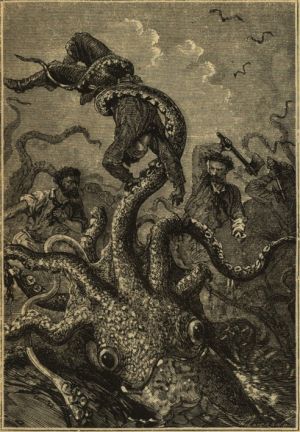

The elusive nature of the giant squid and its terrifying appearance have firmly established its place in the human imagination. Representations of the giant squid have been known from early legends of the Kraken through books such as Moby-Dick and Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea to modern animated television programs.

In particular, the image of a giant squid locked in battle with a sperm whale is a common one, although the squid is, in fact, the whale's prey and not an equal combatant.

References

See also

- Colossal Squid

- Kraken

- Lusca

- Cthulhu, an alien creature with a cephalopod like appearance from the H.P. Lovecraft story The Call of Cthulhu.

- Gigantic octopus

Sources

- Richard Ellis 1998. The Search for the Giant Squid. Lyons Press (London).

- National Geographic Video: "Sea Monsters"

- Aldrich, F.A. & E.L. Brown 1967. The Giant Squid in Newfoundland. The Newfoundland Quarterly. Vol. LXV No. 3. p. 4–8.

- Holroyd, J. New squid on the (ice) block, The Age, 21 December 2005.

- Grann, D. The Squid Hunter. New Yorker, May 24, 2004.

External links

- [First-ever observations of a live giant squid in the wild.]

- Tree of Life Web Project: Architeuthis

- Researchers catch giant squid

- [1] - Video of a giant squid

- BBC News Report

- Holy Squid! Photos Offer First Glimpse of Live Deep-Sea Giant

- TONMO.com's fact sheet for giant and colossal squids

- TONMO.com's giant squid reproduction article

- Reuters: Video of Giant Squid

- Encounters with Giant Squid

- 15 January, 2003, Giant squid 'attacks French boat'

- Cephalopod taxonomy (as PDF)

- Scientific report in Proceedings of the Royal Society

- In Search of Giant Squid - Smithsonian Institution Exhibition

- New Zealand - 1999 Expedition Journals In Search of Giant Squid